Injury Prevention in Basketball

Injuries & Athlete Management

For anyone that has been sidelined with an injury, it can be a physically and mentally challenging experience. Being unable to contribute on the court to the success of the team is never a position an athlete wants to endure. Sadly, it is too often a part of the process, but with proper management and preparation the chances of injury decrease greatly.

There is a responsibility for coaches, parents, and athletes to take a proactive approach in decreasing the rate of injury and allowing the experience on the court to be productive (10).

How to Prevent Basketball Injuries

This article is going to discuss the numerous injury risks found in basketball and provide guidelines to mitigate these risks and allow for improved performance on the court. Some more controllable than others, but all need to be appreciated.

Some of those risks and guidelines include:

- Measuring Internal & External Stressors

- Fatigue & Overuse

- Acute & Chronic Capacity vs Load

- Psychological & Social Factors

- Fitness Level & Progression

- Physical Development

- Weakness & Instability

- Flexibility & Mobility

- Stability & Balance

- Individualized Training

- Movement Mechanics

- Training Habits

- Posture & Core Strength

- Sleep Hygiene

Load Management

One of many pieces that needs to be managed is the stress an athlete is experiencing. This is where the advent of GPS technology has impacted the way sport is managed at the collegiate and professional levels. Sport science groups, as well as researchers, are collecting information and analyzing data on the speeds, contacts, accelerations, decelerations, and jumps occurring within practice and competition. Through these metrics, sport scientists have created a term known as ‘Player Load,’ and it is a measure of both internal and external stressors that an athlete experiences in an individual game or practice and ultimately adds up across the days, weeks, and months of practice, competition, and life.

This is something to consider as fatigue is the leading cause of injury. When we often think that the answer is to do more and work harder, sometime the answer is to work smarter.

Do less. Manage fatigue and increase recovery by reducing the quantity and promoting more quality.

Related to managing fatigue and recovery, overuse injury (e.g., stress fractures or patellar tendinitis) can be common as an athlete is still growing and developing (19). Combining this development period with the repetitive stress of basketball puts the athlete at greater risk as the trauma adds up (10). Inflammation, aches, and pains in joints, tendons, and bones should not be ignored or suppressed with medication.

A young athlete must listen to what their body is trying to tell them and respect their readiness to play versus their need to rest.

No GPS? No Problem - How to Monitor Player Load

Even without the opportunity of GPS or any other sport technology, the concept of ‘Player Load’ should still be appreciated. The concept allows the value to be specific to the individual athlete and is a combination of internal and external stressors.

The external stressor could be as simple as noting the total practice time in minutes or hours and multiplying that by the player’s rating of how intense that practice was on a scale of 1-10 (10 being most intense), their ‘Rate of Perceived Exertion’ (RPE).

Practice Minutes x Player’s RPE = ‘Player Load’ for that session

This would provide the coach and athlete with a combined internal and external value. Another opportunity for a coach or athlete to gauge athlete recovery and readiness is to ask simple questions prior to practice beginning. On a scale of 1-10 how ‘ready’ does the athlete feel? Are they motivated? Fatigued? Sore? All of these are questions that help to provide an understanding of internal stressors that can impact the overall ‘Load’ that the athlete is experiencing.

Evaluating an athlete’s personality and life stressors can help create opportunity for potential psychological intervention that improves enjoyment, attitude, and productivity in training (33).

These values are potentially warning signs for ‘Player Load’ that is more than an athlete can handle. We want to avoid that, as well as any abrupt spikes in loading an athlete at the start of a season. Conversely, appreciating the time demands and athlete feedback can provide confidence for a coach in keeping his players out of harms way when it comes to an injury based on fatigue and under recovery.

Injury prevention is a learning process that evolves over time through experience and understanding, with communication and teamwork being of utmost importance (4).

The first step in injury prevention is managing the load an athlete is carrying.

Load < Capacity

An injury can occur when the load an athlete experiences exceeds his/her capacity. Capacity is a measure of ability, a value of how much. How much can they endure? How strong or durable is a specific bone, muscle, or joint? A basketball player experiences numerous forces and stress from all the running, jumping, shooting, cutting, pivoting, dribbling, not to mention the physical contact from other players.

Over 50% of the injuries that occur in basketball impact the hip, knee, or ankle. Anything from a painful ankle sprain to the dreaded season ending ACL tear.

An athlete’s capacity is their ability, both acute (i.e., immediate or short-term) and chronic (i.e. long-term). Their capability to handle the landing of a layup under the pressure and contact of a defender, as well as in the ability to both recover from multiple practices, games, and workouts.

Gabbett TJ, The training—injury prevention paradox.

Gabbett TJ, The training—injury prevention paradox.British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016; 50:273-280.

Every athlete has a capacity that is specific to them based on their genetics and development over time. Load can exceed capacity slowly over a season with improper recovery, as well as in one instance if a specific or unexpected action is greater than the body can withstand, or even a combination of the two.

This is why we see a lot of injuries at the start of the season as athletes go from doing very little to doing a lot in a short period of time (i.e., a spike in load).

Likewise, there is a rise of injuries during times of high stress at school with final exams.

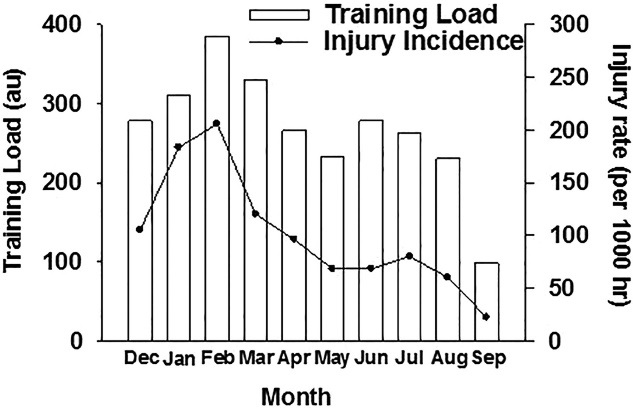

Lastly, we see a lot of injuries at the end of a season as the aches and pains have added up (i.e., chronic), recovery and the concept of ‘Player Load’ has been ignored and fatigue grows across the season and reaches its peak when it matters most during an intense championship tournament with condensed competition (see image to the right, 12). All of these are examples of situations an athlete does not want to be in and can avoid.

An athlete’s capacity is something to develop and improve, and this is where the concept of injury prevention comes into play. Ben Franklin had a saying – “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Originally in reference to fire safety, Ben Franklin’s saying applies here as well with steps an athlete can take to improve durability and better handle the demands that basketball places on the body.

As we address the idea of Injury prevention, it is not one thing, but rather a combination of everything from fitness level, flexibility, muscle strength, joint stability, balance, coordination, psychological and social factors (8).

Progress is a Process

The sport of basketball is very repetitive and in starting a season, athletes often do too much too soon, without proper preparation, training, and recovery. This is where off-season and pre-season training have a huge impact on the opportunity to compete and handle the stresses of the increase in playing and practice time on the court.

It is vital that an athlete takes the time to prepare themselves physically with a combination of both on-court skill work, as well as a structured strength, jump, and conditioning program to improve their overall fitness level. The same is said for when injury does occur, that proper rehabilitation, reconditioning, and return to play occur, as the risk factor most consistently associate with an increase in injury risk is previous injury (10).

It is better to prevent an injury than repair it (15).

Proper training and development prior to the season can help to solidify proper mechanics. Just as a baby learns to crawl before he walks and walks before he runs; performing things at speeds slower than game tempo and respecting the idea that perfect practice makes permanent, progression through an off-season is key. A young athlete needs to be patient and build things slowly over time. With proper preparation and proper mechanics, the athlete is gaining the ounce of prevention that Mr. Franklin was talking about. Prevention that keeps an athlete on the court and impacting the game and team.

Games are Won Before They are Played

The greatest athletes get to where they are through hours and hours, repetition after repetition of shooting, ball handling, jumping, cutting, as well as training off the court in the weight room. This is where the saying, “games are won before they are played” holds true.

If an athlete wants the chance to be great, to be on the court when the game is on the line, he or she needs to not only develop a great jump shot, but also needs to develop the necessary strength and durability to increase capacity and maximize opportunity.

Nature of Injuries – Athletic Development

The lower body musculoskeletal injuries that can plague a basketball player are often non-contact in nature and come as a result of:

- Fatigue

- Surprise

- Loss of concentration

Basketball is a very physical game and contact comes from defensive pressure, falling, cutting, or rebounding; all of which create unexpected loads on the hips, knees, and ankles of an athlete. Strength in these areas is vital.

Rapid hormonal changes of a prepubescent athlete not only influence growth, but also impact self-control and risk perception (10). Not to mention, adolescent athletes mature and develop at different rates, often times putting athletes on the court together that are not nearly as physically and biologically mature as others.

Females especially have a very high incidence of injuries, with upwards of 10% of collegiate players experiencing an ACL injury (17). This increased risk is due to greater joint laxity, lower strength levels, and decreased proprioception and coordination compared to their male counterpart (11, 17, 23).

These lower body injuries come from instability and weakness and happen because the immediate load exceeds the capacity of that structure. Whether the action is a buckling crash of the hip or knee, an aggressive pivot that causes a sprain, or a quick crossover that rolls the ankle.

Injuries occur as a result of

- Poor trunk control

- Hip Instability

- Inward (valgus) crash of the knee

- Ankle and Foot Instability

As an athlete grows it is important to strengthen these areas, increase capacity, and provide necessary durability to prevent injury. Simply playing basketball is not enough, an athlete needs to use the weight room and prepare for the forces and actions he or she will experience on the court that exceed their own bodyweight.

How to Train – Where to Focus

Just as one must learn proper mechanics in shooting a free throw, developing proper movement mechanics as it relates to squatting, lunging, jumping, cutting, and landing is important in maximizing potential and properly align limbs to manage forces (28).

Combined with great skill, the athletes that are the strongest and most powerful have the potential to be the most dominant on the court, as well as the most durable.

With great power, comes great responsibility, an athlete must learn to use their strength on the court and move efficiently if he or she wants to be effective.

Movement efficiency is a combination of:

- Mobility

- Stability

- Balance

- Posture

An athlete that is both mobile and stable in the shoulders, trunk, hips and ankles helps to improve balance and posture, protecting the body and knee from injury and lead to improved performance.

Simply learning to move efficiently with bodyweight is an athlete’s first step to properly managing the forces and stresses of basketball, using and moving as the body was intended to be used and loaded.

With the ability to maintain proper posture, balance, and provide stability to prevent injury.

Muscles AND Movements

This is where the weight room addresses the concept of movements and muscles. Using proper movements, adding load to them and teaching the brain to engage proper muscles, such as the glutes and quads, to contract and stabilize the hip and knee.

Proper & Progressive

Through proper and progressive strength training, an athlete develops the ability to recruit muscles, necessary stiffness in tendons, and exposing joints (e.g., hip and ankle) to full ranges of motion. Strength training develops symmetry and aims to eliminate weakness or imbalance.

Remember the goal is not bodybuilding, but rather performance and prevention focused. Although there are performance benefits from increasing muscle mass, as well as preventing injury through increasing the structure and frame of an athlete; the immediate goal of strength training is the neuromuscular benefits associated with proper activation and function.

With improvements in neuromuscular function, an athlete learns to properly decelerate. Movements such as loaded squats and lunges help to create awareness of proper posture and alignment of the spine and torso, creating awareness and stability of foot pressure, as well as engaging musculature (e.g., glutes, quads, hamstrings, and calves) that stabilizes the lower body.

An athlete should always focus on proper technique and never sacrifice load for mechanics. Compensation in a basic movement is going to be a weakness and limitation on the court.

Ultimately strength training helps the athlete learn to create tension and stiffness in positions found on the court during play.

Adapt the Training to the Athlete

It is vital that the training program be specific to the athlete and their developmental age.

Young athletes are not mini adults, implementing training needs to be done with care and caution. Loading appropriately and progressively, individualizing and adapting the program to the athlete’s needs and ability. Young athletes have open growth plates, growing cartilage that is very susceptible to the stresses of sprinting, jumping, and cutting.

This is why strength training is important to implement sooner than later because it will aid in the developing neuromuscular function, coordination, motor control, and proprioception.

Any age is appropriate for strength training – be sure to load appropriately, safely, and progressively:

- Avoid pain

- Bodyweight First

- Technique Always

Not to mention that with improved neuromuscular function comes increased force production. Creating an athlete that is more explosive, can jump higher, and sprint faster.

Variety is the Spice of Life

Strength training is great, but there is a lot more that goes into preparing for the demands of basketball. The reactive and unpredictive nature of basketball requires movements in all planes of motion (i.e., sagittal, frontal, and transverse) and movement patterns in training should address the same. Working in numerous and various patterns that challenge and prepare the mind and body for competition.

Variety in training is very important to prevent injury and developing a broad range of abilities.

If You Don’t Have Time to Warm Up, You Don’t Have Time to Train

Proper warm-up can also be a great preparation tool that has shown to prevent injury (32). Dedicating time to properly warming up increases:

- Blood flow

- Core Temperature

- Heart Rate

- Rate and Efficiency of Muscle Contraction

- Neuromuscular Function

A proper warm-up includes both general and specific preparation, incorporating dynamic and active movements. Employing these strategies further yields positive results in preventing injury (36). Stretching and preparing tissues for more intense activity. This should happen both before a lifting session or practice on the court. Don’t fall victim to the “train to warm-up” mentality, instead “warm-up to train.”

Consistency is Key - Creating habits, rituals, and being consistent with principles of training and recovery lead to optimal growth, development and durability.

Ancillary Training Means

Locomotion – Activities that include running, jumping, cutting, and shuffling that lead to guarding, driving, and reacting are also progressive. Starting simple and progressing to more reactive and unpredictive movements or drills can improve development, awareness, and anticipation. These functional movements aid in injury prevention through preparation of awkward landings and foot contacts (29). This helps the athlete manage their newfound strength and force producing capabilities. Addressing movement mechanics and techniques.

Flexibility - As adolescent athletes go through puberty, there is a rapid growth in height and bone length, but muscles and tendons can present tight as they develop at different rates (10). This further impacts and stresses joints and ligaments, increasing the need to be used properly in training to develop their full potential and prevent injury. This occurs before, during and after training and taking time to properly stretch and move. Stretching following warm up can prevent muscular injuries (39). Sitting in the car, class, or at home can create issues with posture and decrease flexibility. Stretching is another means of injury prevention in this regard. If an athlete finds themselves with a lack of flexibility, stretching three times per day (e.g., morning, noon, and night) is necessary to see lasting change.

Core Training - Studies show that not only does core training enhance an athlete’s vertical leap and improve movement patterns, but also prevents injury, improving lower limb and trunk biomechanics (31).

Balance Training - Supporting our concept of variety, incorporating implements such as a balance beam or performing exercises in a single leg stance. Further focusing on muscle activation, neuromuscular control, and stabilization are shown to prevent injury (21). Finding and prescribing ways to challenge movements and incorporate visual and reaction cues while doing so. Training that improves balance, coordination, and postural control aids in injuries to the knee and ankle (25). Careful not to get too cute or fancy and try to do too much. This kind of training may be challenging but it is not strength training. Strength is developed through load, tension, and contraction. Careful not to mix the two and limit the benefits of proper strength training. All in all, it does have its time and place in preventing injury and thoroughly developing an athlete.

Increasing Capacity through Recovery

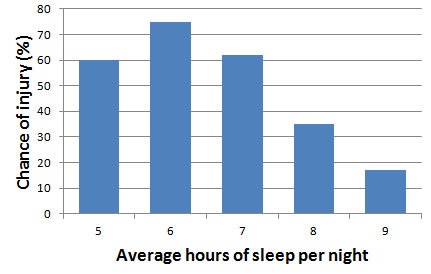

The strength and development an athlete experiences through an off-season can only be showcased through proper recovery and lifestyle habits off the court as well. As we said, fatigue is the leading cause of injury, and fatigue is primarily a measure of how much and how well an athlete is sleeping.

Milewski, M. D., Skaggs, D. L., Bishop, G. A., Pace, J. L., Ibrahim, D. A., Wren, T. A., & Barzdukas, A. (2014). Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 34(2), 129-133.

Milewski, M. D., Skaggs, D. L., Bishop, G. A., Pace, J. L., Ibrahim, D. A., Wren, T. A., & Barzdukas, A. (2014). Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 34(2), 129-133.

Research shows that, hours of sleep per night and the grade in school were the best independent predictors of injury (27). Showing that “athletes who sleep on average <8 hours per night have 1.7 times greater risk of being injured than those who sleep = 8 hours (27).”

Encouraging young athletes to get optimal and maximal amounts of sleep may help protect them against injuries on the court. Strategies to improve sleep hygiene and environment are productive steps an athlete needs to adopt and commit to.

Other controllable Factors

Even with proper preparation and recovery, the risk of injury still ensues. Further steps such as proper footwear and lacing them properly. A shoe that provides proper support of the foot and ankle. As well as, minimizing risk by ensuring the playing surface is dry and clear of wet spots or hazards that could cause an athlete to fall or trip.

Summary

The final choice is yours, injury prevention takes time and commitment, and focusing on what you can control. All parties (e.g. parents, coaches, practitioners, and athletes) have a responsibility to work together and do what’s best as a young athlete develops.

The process begins with proper education and understanding. Individuals need to work together to consistently implement a structured program that fits the situation of the athlete (10). This may include some sort of financial commitment, but is an investment shown to provide a great return. Coaches need to continue to encourage technique and implementation through proper supervision and feedback, aiding in the proper execution of exercises (28). Using a team approach, identifying barriers and developing solutions, with proper planning and progression of improvement is what allows for injury prevention (16).

In the end, commitment and consistency is key, and the ounces of prevention add up to allow an athlete a healthy, productive, and successful career.

Additional Resources

- Athletic Development Program to Improve Speed, Strength and Vertical Jump

- Strength, Conditioning, and Agility Resources for Basketball Players

References

1. Adirim TA, Cheng TL (2003) Overview of injuries in the young athlete. Sports Med, 33, 75–81.

2. Backx FJ, Erich WB, Kemper AB, Verbeek AL: Sports injuries in school-aged children – An epidemiological study. Am J Sports Med 1989;17:234–240.

3. Backx FJ, Beijer HJ, Bol E, Erich WB: Injuries in high-risk persons and high-risk sports – A longitudinal study of 18118 school children. Am J Sports Med 1991;19:124–130.

4. Bolling, C., Barboza, S. D., van Mechelen, W., & Pasman, H. R. (2019). Letting the cat out of the bag: athletes, coaches and physiotherapists share their perspectives on injury prevention in elite sports. British Journal of Sports Medicine, bjsports-2019.

5. Cassas KJ, Cassettari-Wayhs A (2006) Childhood and adolescent sports-related overuse injuries. Am Fam Physician, 73, 1014–1022.

6. Chandy TA, Grana WA: Secondary school athletic injuries in boys and girls: A three-year comparison. Phys Sportsmed 1985;13:106–111

7. DuRant RH, Pendergrast RA, Seymore C, Gaillard G, Donner J: Findings from the Preparticipation Athletic Examination and athletic injuries. Am J Dis Child 1992;146:85–91.

8. Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH, Hartmann SE (2005) Evaluation of risk factors for injury in adolescent soccer: implementation and validation of an injury surveillance system. Am J Sports Med, 33, 1882–1891.

9. Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE: Valgus knee motion during landing in high school female and male basketball players. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999;35:1745–1750.

10. Frisch, A., Croisier, J. L., Urhausen, A., Seil, R., & Theisen, D. (2009). Injuries, risk factors and prevention initiatives in youth sport. British medical bulletin, 92(1), 95-121.

11. Frisch A, Seil R, Urhausen A, Croisier JL, Lair ML, Theisen D (2008) Analysis of sex-specific injury patterns and risk factors in young high-level athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports, in press.

12. Gabbett TJ The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016; 50:273-280.

13. Gomez E, DeLee JC, Farney WC: Incidence of injury in Texas girls’ high school basketball. Am J Sports Med 1996;24:684–687.

14. Gunnoe AJ, Horodyski M, Tennant LK, Murphey M (2001) The effect of life events on incidence of injury in high school football players. J Athl Train, 36, 150–155.

15. Harmer, P. A. (2005). Basketball injuries. In Epidemiology of Pediatric Sports Injuries (Vol. 49, pp. 31-61). Karger Publishers.

16. Hayley J. Root, Barnett S. Frank, Craig R. Denegar, Douglas J. Casa, David I. Gregorio, Stephanie M. Mazerolle, and Lindsay J. DiStefano (2019) Application of a Preventive Training Program Implementation Framework to Youth Soccer and Basketball Organizations. Journal of Athletic Training: February 2019, Vol. 54, No. 2, pp. 182-191.

17. Hewett TE, Lindenfeld TN, Riccobene JV, Noyes FR (1999) The effect of neuromuscular training on the incidence of knee injury in female athletes. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med, 27, 699–706.

18. Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR et al. (2005) Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med, 33, 492–501

19. Hickey GJ, Fricker PA, McDonald WA (1997) Injuries of young elite female basketball players over a six-year period. Clin J Sport Med, 7, 252–256

20. Hogan KA, Gross RH (2003) Overuse injuries in pediatric athletes. Orthop Clin North Am, 34, 405–415.

21. Huxel Bliven, K. C., & Anderson, B. E. (2013). Core stability training for injury prevention. Sports health, 5(6), 514-522.

22. Junge A (2000) The influence of psychological factors on sports injuries. Review of the literature. Am J Sports Med, 28, S10–S15.

23. Jones D, Louw Q, Grimmer K (2000) Recreational and sporting injury to the adolescent knee and ankle: prevalence and causes. Aust J Physiother, 46, 179–188.

24. Kolt G, Kirkby R (1996) Injury in Australian female competitive gymnasts: a psychological perspective. Aust J Physiother, 42, 121–126.

25. McGuine TA, Greene JJ, Best T, Leverson G (2000) Balance as a predictor of ankle injuries in high school basketball players. Clin J Sport Med, 10, 239–244.

26. Messina DF, Farney WC, DeLee JC: The incidence of injury in Texas high school basketball. A prospective study among male and female athletes. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:294–299.

27. Milewski, M. D., Skaggs, D. L., Bishop, G. A., Pace, J. L., Ibrahim, D. A., Wren, T. A., & Barzdukas, A. (2014). Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 34(2), 129-133.

28. Olsen OE, Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, Holme I, Bahr R (2005) Exercises to prevent lower limb injuries in youth sports: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br Med J, 330, 449.

29. Peate, W. F., Bates, G., Lunda, K., Francis, S., & Bellamy, K. (2007). Core strength: a new model for injury prediction and prevention. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 2(1), 3.

30. Powell JW, Barber-Foss KD: Sex-related injury patterns among selected high school sports. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:385–391.

31. Sasaki, S., Tsuda, E., Yamamoto, Y., Maeda, S., Kimura, Y., Fujita, Y., & Ishibashi, Y. (2019). Core-Muscle Training and Neuromuscular Control of Lower Limb and Trunk. Journal of athletic training.

32. Soligard, T., Myklebust, G., Steffen, K., Holme, I., Silvers, H., Bizzini, M., ... & Andersen, T. E. (2008). Comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in young female footballers: cluster randomised controlled trial. Bmj, 337, a2469.

33. Steffen K, Pensgaard AM, Bahr R (2008) Self-reported psychological characteristics as risk factors for injuries in female youth football. Scand J Med Sci Sports, in press.

34. Taylor B, Attia MW: Sports-related injuries in children. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:1366–1382

35. Watson AWS: Sports injuries during one academic year in 6799 Irish school children. Am J Sports Med 1984;12:65–71.

36. Wedderkopp N, Kaltoft M, Holm R, Froberg K (2003) Comparison of two intervention programmes in young female players in European handball—with and without ankle disc. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 13, 371–375.

37. Wedderkopp N, Kaltoft M, Lundgaard B, Rosendahl M, Froberg K (1999) Prevention of injuries in young female players in European team handball. A prospective intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 9, 41–47.

38. Willems TM, Witvrouw E, Delbaere K, Mahieu N, De Bourdeaudhuij I, De Clercq D (2005) Intrinsic risk factors for inversion ankle sprains in male subjects: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med, 33, 415–423.

39. Woods K, Bishop P, Jones E (2007) Warm-up and stretching in the prevention of muscular injury. Sports Med, 37, 1089–1099.

|

|||

Facebook (86k Likes)

Facebook (86k Likes) YouTube (131k Subscribers)

YouTube (131k Subscribers) Twitter (29.8k Followers)

Twitter (29.8k Followers) Q&A Forum

Q&A Forum Podcasts

Podcasts